https://www.thejakartapost.com/paper/2021/01/11/revolusi-a-reappraisal-of-indonesias-awakening-history.html

The Jakarta Post 12 Jan 2021

By Aboeprijadi Santoso – An Indonesian journalist residing in Amsterdam

When then-Dutch prime minister J.P. Balkenende urged the Parliament in 2006 to recall the Golden Age of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), there was some indignant booing.

“[We need] VOC mentality!” the PM replied angrily.

That was a moment that fed into the narrative of the “pride and shame, emancipation and humiliation, hope and violence” of Dutch history, the Belgian historian David van Reybrouck wrote. The VOC, after all, was responsible for genocide there.

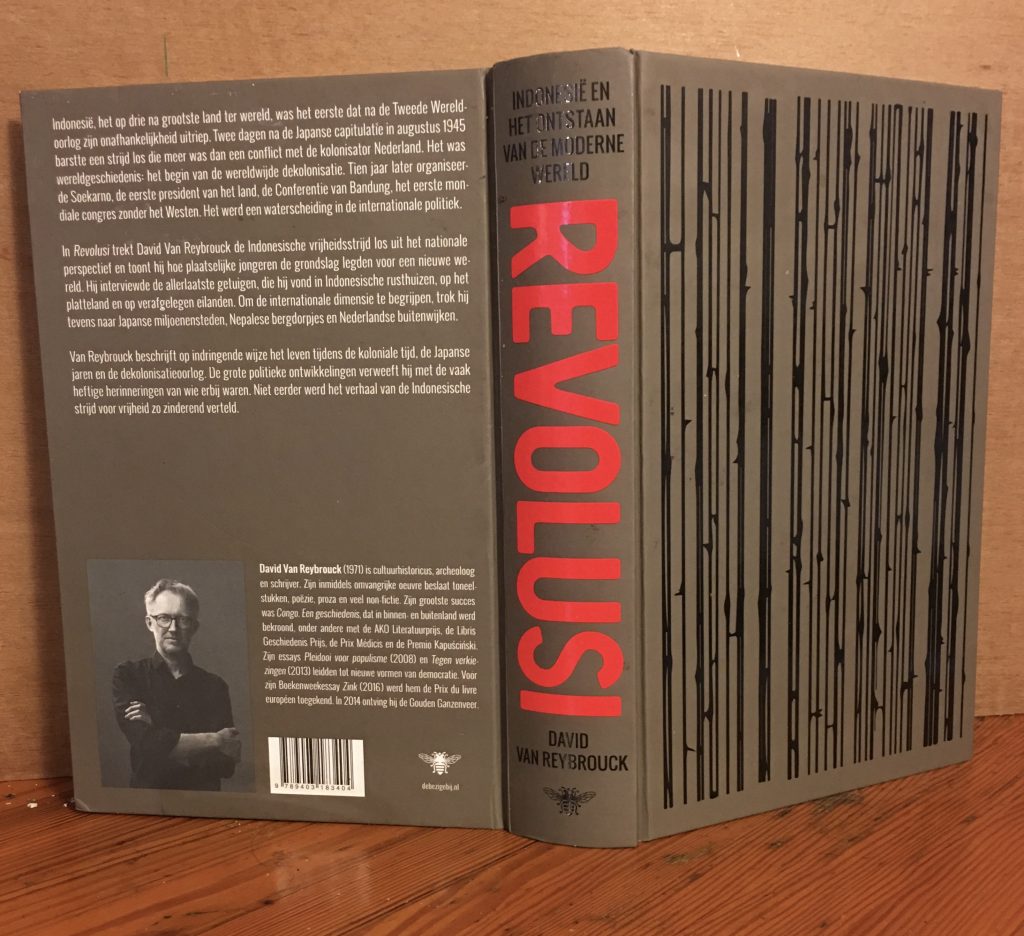

Van Reybrouck’s new book Revolusi, Indonesie en het ontstaan van de moderne wereld (Revolution, Indonesia and the Emergence of the Modern World) has been widely praised in the Netherlands – much as his earlier work on the Congo.

The book (637 pages) is an attempt to review Indonesian history by exploring how Dutch colonialism was more disastrous than other European powers elsewhere. Van Reybrouck describes colonial policies and emphasizes the way the indigenous society responded from the early decades of the last century, only to conclude that it emerged as the first independent country that called ex-colonies elsewhere to arise.

He, thus, describes how the archipelago radically changed from mere a small VOC spice warehouse in Ambon, Maluku, to become the world’s fourth-largest nation. When the company that collected huge profits by forging a violent monopoly went bankrupt, the islands fell prey to European colonialism: the British, the French and the Dutch. It ultimately led to the great Java War (18251830) that took some 200,000 human lives and devastated the land.

Interestingly, the writer dealt with Dutch colonialism, the Japanese period and the independence struggle along the themes of violence, militancy and diplomacy. Although the Japanese were welcomed at first and the occupation was truly decisive in releasing the leaders of the nation who were captured by the Dutch, they made millions suffer and hungry as never before. Yet it helped raise the militancy and violence of the people militia’s during the independence struggle.

When the Dutch returned, he found out, its soldiers did not seem to be aware of the true pattern of their war — the structural violence, that is, which historian Remy Limpach revealed, implying what the Dutch eminent historian L. de Jong once described as “war crimes” — that occurred during the aggression wars in 1940s. Some 200,000 on the Indonesian side and 50,000 Dutch were killed.

This is an attempt to settle the endless debate in terms of victimhood that has dominated the Dutch media, which can also be seen when the writer dealt with racism and the position of the Indo-Europeans, the Indos as part of the colonial elite and later as a forgotten section in Dutch postwar society.

Finally, the diplomacy saved the nation. The trouble the Dutch made with the Linggadjati and Renville agreements, coupled with Van Mook’s Malino attempt to divide the nation, ultimately failed to materialize as the Roem-Royen deal restored the nation’s independence and sovereignty over the whole archipelago.

All of this was mainly thanks to the Americans. The fact that the late 1940s postwar world was soon caught by the Cold War meant that the United States was more interested and worried about communism than helping the Dutch restore power in Indonesia.

The whole trajectory led the writer to name the years around 1914 as the early awakening moment of the indigenous society. Unlike the Europeo-centric writers whom J. C. van Leur saw as writing “from the ship deck”, van Reybrouck listened to witnesses and their relatives.

Curiously, he covered almost one and a half centuries of colonialism into the independent war by traveling half the world over – from North Maluku to Java, Bali, Sumatra, Japan, even Nepal (on the Gurkha’s) and the Netherlands to find, meet and interview almost 200 elderly witnesses on some historic persons and events.

Many of them were rarely heard of, but the oral history method he loved and applied helped elucidate the events and made the book lucid and colorful.

Take for example the cases of Djajeng Pratomo and Francisca (Cisca) Pattipilohy. Djajeng (19142018), a descendant of a Javanese prince, was with the Perhimpoenan Indonesia in Leiden when he joined the Dutch resistance against fascism and his compatriots’ struggle for Indonesia’s independence. The Djajeng-Stennie (his Dutch wife) story was one of a love-cum-solidarity and fight that was little-known at home but vividly illustrates the Zeitgeist.

So, too, is Cisca’s story ( b.1926). A daughter of a well-to-do Maluku family, she has lived through four radically different eras – the colonial one with its deep-felt racism-based injustice she cannot forget, the Japanese occupation, the independence struggle and the 1960s – only to end up exiled in the Netherlands when her husband, a journalist, was arrested by the Soeharto regime and disappeared.

The rich Dutch sources, excellent studies and witnesses whom Reybrouck met and helped him telling the stories explain the dynamic, happy, tragic, sometimes decisive events that went with the struggle of the new nation.

So, if Muslim politics started at H.O.S. Tjokroaminoto’s home in Surabaya, East Java, where youth activists, including Sukarno, met each other, communism began in Semarang, Central Java, with Dutch union leader Henk Sneevliet, and nationalism in Leiden with Djajeng Pratomo and Mohammad Hatta.

The book, thus, describes Surabaya, Semarang and Leiden as the vocal starting points of the nation’s awakening and resistance. It ends with Cisca narrating that the mass killings of 19651966 came to halt the revolusi (revolution). That bloody method, coded Operacao Jacarta, was later “exported” to Latin America. The imperialists won. Cisca: “Then, everything is lost.”

In between, Reybrouck provides a vision of how Indonesia, having achieved independence, contributed to the awakening of the colonized world by inviting the new nations, the ex-colonies, to the Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung, West Java, in April 1955 — the first momentous, international and historic gathering of independent countries without the West, he emphasizes.

That was a “meeting of the rejected”, the black writer Richard Wright put it, of those who were “despised, insulted, hurt and dispossessed” in the past.

“A universal event,” said a French observer, comparing it to the French Revolution and US Declaration of Independence.

The US was not happy (“the voice of the Free World must stifle the voice of the communism”) watching Sukarno, Nehru, Nasser and the smiling Zhou Enlai walking proudly on the streets of Bandung.

It created a flurry of diplomatic discourse and awakening in Asia and most parts of Africa as its echoes are still heard even today.