https://www.thejakartapost.com/paper/2023/01/17/justice-for-post-genocide-reconciliation.html

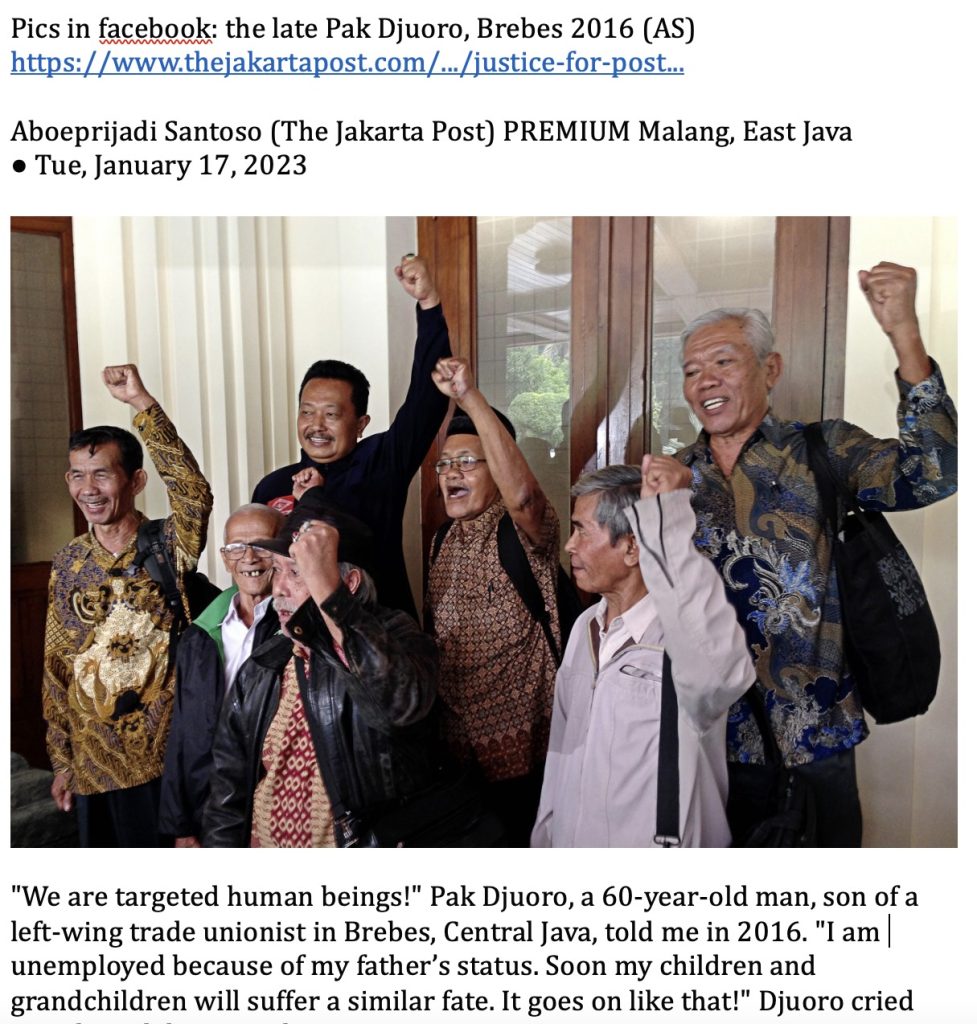

“We are targeted human beings!” Pak Djuoro, a 60-year-old man, son of a left-wing trade unionist in Brebes, Central Java, told me in 2016. “I am unemployed because of my father’s status. Soon my children and grandchildren will suffer a similar fate. It goes on like that!” Djuoro cried angrily and desperately.

The political stigma against him was hereditary. The mass killings and disappearance of those in the mid-1960s remain chronicled in the memories of many like him.

President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s acknowledgment of the great tragedy will not change much of their fate.

Last week, the President expressed “deep regret” over the 1965-1966 mass killing and 11 other past atrocities. No mea culpa, no apology.

The commission that will investigate the crimes against humanity said the cases would be subjected to a judicial process or a so-called “non-judicial” one, a sort of truth and reconciliation process.

The decision applies to the gross human rights violations that took place during and after Soeharto’s rule, from the mass killings in 1965-66 and in 1973-1975 at Soeharto’s behest, the kidnapping of activists led by Lt. Gen. Prabowo Subianto’s men just before the fall of Soeharto, the Trisakti killings, the Chinese pogrom in May 1998, the killings of Muslim dukun (soothsayers) in East Java in 1999, the attack on Muslim radicals in Lampung and some atrocities during the conflicts in restive provinces of Aceh and Papua.

Significantly, before handing over the report to the President, the commission held a special meeting in October 2022 with the Pepabri, a powerful body of retired military officers. In doing so, they were very concerned. Indeed, some retired generals asked with a dismissive tone whether the investigators would point their finger at the culprits and whether those who fought to defend the unitary state would also be tried.

The latter refers to the soldiers involved in the atrocities during the wars in Aceh and Papua. The message is clear: They will reject the state’s apology and therefore there is no trial for those involved.

East Timor, now Timor Leste, was not mentioned at all. The commission led by experienced diplomat Makarim Wibisono includes Lt. Gen. (ret) Kiki Syahnakri, the man who knows East Timor well and speaks the language, who had to withdraw from the Indonesian army after the bloody 1999 referendum.

The militia violence during the period, under the authority of Gen. Wiranto and an interdepartmental body led by Gen. Feisal Tanjung, has never been fully tried. The issue ended with a treaty of friendship with the new state of Timor Leste (the Timor Leste-Indonesia Commission of Truth and Friendship 2008).

In the process, the entire period of the civil war, the invasion, and war in 1975-1979, with almost a third of the civilian population killed and a number of atrocities committed such as those in Kraras, Santa Cruz, Liquica and Suai, all were wiped off the agenda.

One should also question what cases the commission would cover in Aceh and Papua. The killing of Teungku Bantaqiah in Aceh at the behest of a local army commander, for example, was not included.

One wonders about the Biak killings in July 1998 and, more recently, the case of Nduga in Papua, where the population was displaced because of violence.

Most notable, of course, is the issue of the murders, disappearances, and arrests of at least half a million people in 1965-1966. It is not for the first time the Indonesian head of state paid attention to the case.

Former president Abdurrahman “Gus Dur” Wahid floated the idea of the state apologizing to all victims. He even suggested pulling the state decree to ban Marxism and Leninism. His proposals disappeared in the darkness.

Most telling is former president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s attempt in 2014 to offer an apology to the 1965-1966 victims during the Independence Day celebrations on Aug. 17. The idea failed. He was reportedly pressured by a group of generals led by Gen. (ret) Solichin GP and a group of leading Muslims.

They categorically rejected the idea. The former president himself would later seek understanding from the National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM). Sarwo Edhie, the general who led the mass killing in Java, was his father-in-law.

With Jokowi, a former furniture entrepreneur not connected to the networks of the military elite, came to power in 2014 much hope was expected of him, yet in vain.

The social and political impact of the bloody events of the mid-1960s has been tremendous for decades. Experts and activists have long demanded a presidential commission to investigate the 1965-66 issue. Amid growing economic expectations, human rights cases suffer under what has been termed “the institutionalization of impunity.”

President Jokowi’s “deep regret” thus represents just a small progress, a stepping stone, perhaps, that many victims may hope will start the fight for justice and compensation.

The basic fact that matters, however, is that many, if not most, of the victims, are dead, forgotten, or untraceable. Historians have pointed out the killings were actually cases of forced disappearances. People were simply “di-bon” (picked up) from home and murdered. John Roosa speaks of “buried histories.”

Whether justice, social compensation, reparation, and a promise that such tragedy will not happen again will be fulfilled, remains to be seen. Much of what had actually happened, who did what, where, why, and how, will remain in the dark.

With some of the old guards may be shielded from accountability and many of the commanders and civilian perpetrators and victims dead, it is much too late to offer Pak Djuoro and the many other people who suffered from human rights crimes, any justice.

*** The writer is a journalist.