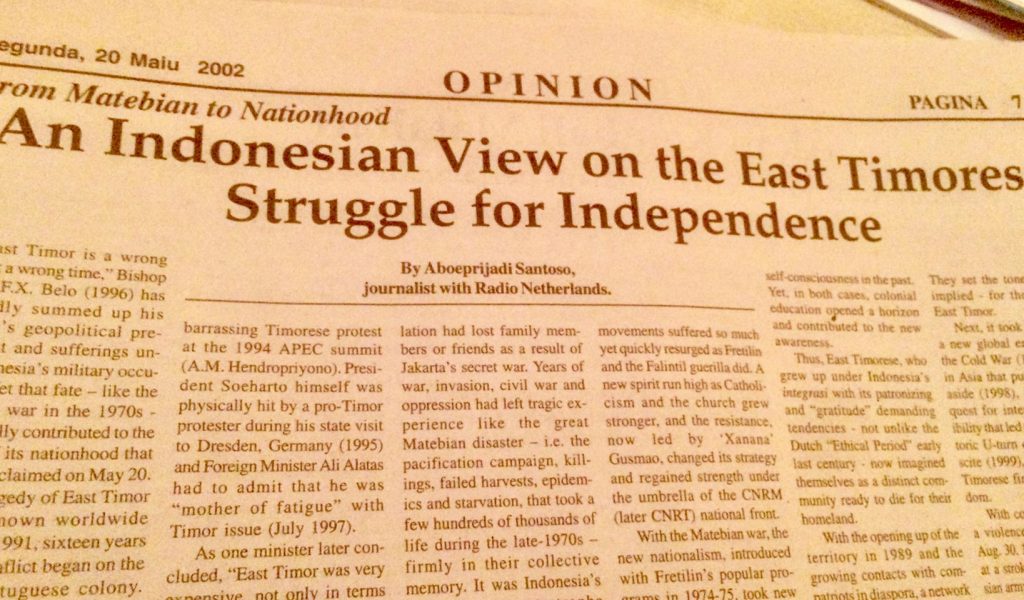

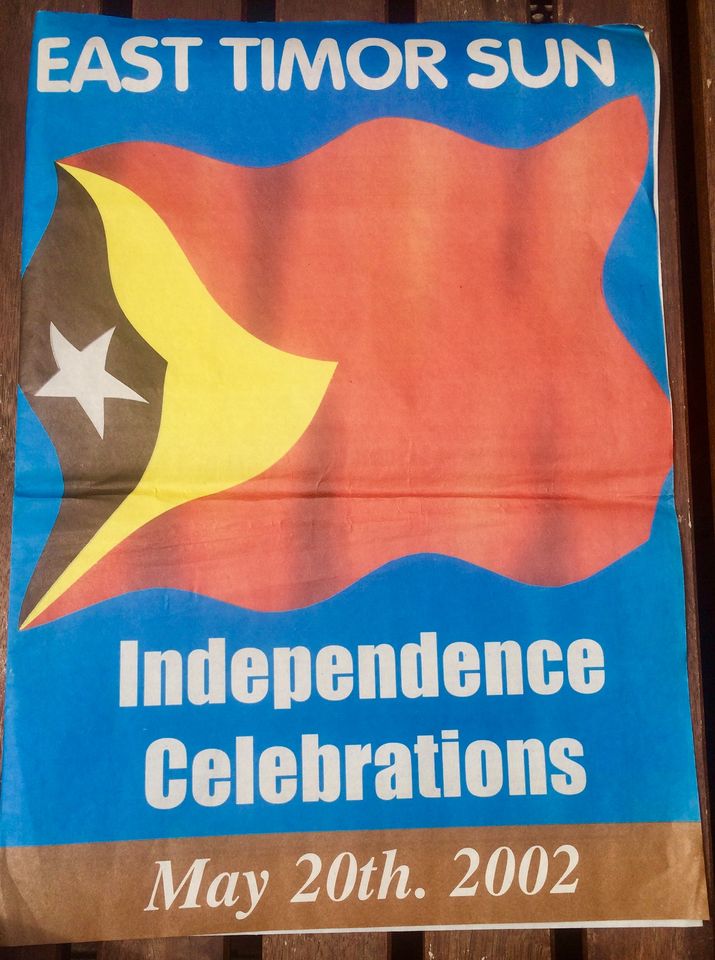

“East Timor is a wrong place at a wrong time,” Bishop Carlos F.X. Belo (1996) has pointedly summed up his country’s geopolitical predicament and sufferings under Indonesia’s military occupation. Yet that fate – like the Matebian war in the 1970s – has crucially contributed to the genesis of its nationhood that will be proclaimed on May 20.

The tragedy of East Timor became known worldwide only since 1991, sixteen years after the conflict began on the former Portuguese colony. But, as abuses continued, already by the mid-1990s the world media were fed up with bad news from the territory. When the Noble Peace Prize was awarded to Bishop Belo and Jose Ramos-Horta in 1996, it was both a reminder and a warning of the international community that the world had recognized, however lately, the legitimate rights of the East Timorese.

In other words, had the island then been decided at a show down at the UN General Assembly, Indonesia might have lost the vote, since its credibility abroad had considerably been damaged and, indeed, had claimed some “victims”.

A number of generals allegedly linked to the Santa Cruz massacre (1991) or earlier atrocities, were removed (R. Warouw 1992), denied an ambassadorship (A.S. Rajaguguk by the U.S. and Japan, and H.L. Mantiri by Australia), missed a top army position (Sintong Panjaitan 1992), even fired after an embarrassing Timorese protest at the 1994 APEC summit (A.M. Hendropriyono). President Soeharto himself was physically hit by a pro-Timor protestor during his state visit to Dresden, Germany (1995) and Foreign Minister Ali Alatas had to admit he was “mother of fatigue” with Timor issue (July 1997).

As one minister later concluded, “East Timor was very expensive, not only in terms of money and materials, but we also have been harassed morally.” Yet Soeharto apparently turned down President Nelson Mandela’s helping hand (Nov. 1997), possibly missing the best – and his last – chance to resolve the issue.

The New Order regime, thus, failed to realize that East Timor, far from being “a gravel in the shoe,” had become Indonesia’s Achilles heel. For, in the end, as the breakthrough only came with the fall of Soeharto (1998) and UN’s self-determination vote (1999), its impact on Aceh soon threatened the unitary state.

If the 1990s were crucial in terms of international momentum, the decade of 1975-85 had been even more decisive in making the East Timorese a nation. The big victory of the former guerilla’s party, Fretilin, at the first general elections last year reveals the depth of the legacy of the 1970s.

After all, most of the population had lost family members or friends as a result of Jakarta’s. secret war. Years of war, invasion, civil war and oppression had left tragic experience like the great Matebian disaster – i.e. the pacification campaign, killings, failed harvests, epidemics and starvation, that took a few hundreds of thousands of life during the late 1970s – firmly in their collective memory. It was Indonesia’s worse human catastrophe since the 1965-66 bloodshed.

A famous method from Indonesia’s own past struggle turned infamous when it was forcefully revived in a sparsely populated, mountainous region. The pagar betis (fence of legs) strategy, aimed to encircle the guerillas, had fatally isolated thousands of their supporters and families for months, forcing many to leave the hills only to be shot as they surrendered.

This annihilation campaign and other cruelties turned the central region of Matebian into a symbol of genocide – a crime for which Soeharto and some generals still enjoy impunity.

Two big campaigns in the early 1980s subsequently wiped out at least the half of the guerilla strengths and almost the entire Fretilin leadership, consisting of a blend of radical socialist, religious-Marxist and nationalist leaders like Nicolai Lobato and Vincente Reis. Few liberation movements suffered so much yet quickly resurged as Fretilin and the Falintil guerrilla did. A new spirit run high as Catholicism and the church grew stronger, and the resistance, now led by ‘Xanana’ Gusmao, changed its strategy and regained strength under the umbrella of the CNRM (later CNRT) national front.

With the Matebian war, the new nationalism, introduced with Fretilin’s popular programs in 1974-75, took new dimensions. East Timor’s experience during the 1970s and 1980s, thus, created a society with a deep hatred against the occupying force and a stronger popular base for the resistance.

Significantly, with this, came the first fully Indonesia-educated Timorese youth – including the surviving children of the Matebian war – who started the uprisings with the Papal visit in 1989 and later joined the resistance. The struggle, though, continued to be led by the Portuguese-trained generation of the 1970s (except Xanana Gusmao) – reminding us to Indonesia’s own awakening in the 1920s led by those educated in Holland rather than homegrown leaders (except Soekarno).

The Indonesian education, imposed on Timorese youth who has sad experience with the Indonesian army, inevitably created a growing alienation – much as the Dutch system aroused self-consciousness in the past. Yet, in both cases, colonial education opened a horizon and contributed to the new awareness.

Thus, East Timorese, who grew up under Indonesia’s integrase with its patronizing and “gratitude” demanding tendencies – not unlike the Dutch “Ethical Period” early last century – now imagined themselves as a distinct community reader to die for their homeland.

With the opening up of the territory in 1989 and the growing contacts with compatriots in diaspora, a network of resistance, loosely unified under the CNRM, was developed. It linked up the clandestine movement inside East Timor and Indonesia, the Falintil guerilla in the hills, and the diplomatic front abroad. Militarily weak yet undefeated, the Timorese resistance – much like the Indonesian freedom fighters in the 1940s – increasingly gained political and diplomatic strength.

The Santa Cruz massacre of Nov. 12, 1991, in Dili acted here as a trigger similar to the U.S. Tonkin bombardment in 1968 for the course of the Vietnamese struggle, or the Sharpsville killings in 1960 for the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. Not the incident, however tragic, but their common experience and resolve in the context of international critics, made the event a key turning point.

Hence, the geopolitics, sufferings and resistance define East Timor’s nationhood. They set the tone – as Belo implied – for the course of East Timor.

Next, it took the dawn of a new global era that ended the Cold War (1989), a crisis in Asia that pushed Soeharto aside (1998), and an urgent quest for international credibility that led to Habibie’s historic U-turn offering a plebiscite (1999), before the East Timorese finally gained freedom.

With courageous votes in a violence-ridden ballot on Aug. 30, 1999, they achieved at a stroke what the Indonesian army feared for decades: a democratic victory. But its aftermath – a de-colonization worse than the Dutch’s in the late-1940s – was an Army-sponsored terror, shameful destruction and massive deportation.

“Let them burn our homes and rob our (properties). I appeal to all my brothers and sister … not to react,” Xanana Gusmao urges his people on Sep. 4, 1999. Playing the victim whilst the UN acted much too late, had cost them very dearly, but the strategy was ultimately successful.

As East Timor is to proclaim its independence on May 20, President Megawati Soekarno Putri’s presence would be important to restore Indonesia’s dignity and offer a true friendship.

*This article is adapted from the presentation given by the author at the George Washington University, Washtington DC, on April 4, 2002.* It was published in Timor Post on May 20, 2002