The article was published Inside Indonesia Edition 56: Oct-Dec 1998 https://www.insideindonesia.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=734:jakarta-s-may-revolution&Itemid=129&tmpl=component

How did Jakarta in May compare with people movements against dictatorships elsewhere in world history?

Aboeprijadi Santoso

Analysts watching Indonesia in May were reminded of two models of change: the 1989 Chinese Tienanmen model and the 1986 Philippine People Power model. Some also thought of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The events in Jakarta turned out to be different to each of them. They were perhaps more bloody than in China. And unlike the total change in the Philippines, transition in Jakarta was quick, but less than total, and filled with tragedy.

In Tienanmen on June 4, 1989, the state’s repressive apparatus used a heavy hand to resolve the crisis. The Chinese authorities managed to preserve the bases of the state, which had been challenged by the students. After making some changes within the elite, they restored stability while limiting further social and economic damage from the three month revolt. Despite five to seven years of diplomatic pain, at the end of the day, a monolithic regime was able to restore the status quo by bloodily crushing opposition forces.

Philippines

The People Power on the Edsa highway in Manila in February 1986, on the other hand, was the reverse of the Chinese solution. Popular anger against Marcos’ dictatorship burst out at every social level. Mrs Corazon Aquino, widow of the popular assassinated senator Benigno Aquino, and Cardinal Jaime Sin provided political and spiritual leadership. The left wing National Democratic Front (NDF) and other movements provided popular opposition platforms. Marcos’ decades of dictatorship had radicalised Philippine society. All that was needed to oust him were some generals to change sides. And this happened at a crucial moment when General Fidel Ramos did just that.

The People Power movement also opened up, and was soon threatened by, internal military rivalries and rebellions. The Rambo game of Colonel Gringo Honasan is the most well known example.

Both revolts were supported at least passively by most sections of society. But the mainly urban student revolt in China was too small and weak to face the state apparatus. In the Philippines, by contrast, the revolt was truly mass based, while the state apparatus was too weak and divided to act against it.

Mixed

Jakarta’s ‘May Revolution’, as the student protests and the fall of Suharto are now called, contained mixed elements. As in China, the imbalance between the student movement and state apparatus in Indonesia was obvious. As in China too, the student rebellion was widely supported by society. However, the Indonesian state leadership – both before and after the fall of Suharto – suffered from a much more serious crisis than their counterparts in China.

The symbolism emanating from student power in Jakarta and Beijing provoked a quicker act of the state than it did in Manila. Like the Chinese, the Indonesian students chose the very locus of the power they challenged as their place of protest. Demonstrations at parliament house in Senayan, Jakarta, signified their opposition to what they saw as the illegitimacy of existing representative bodies. A similar protest at the National Monument had to be cancelled. The symbolism of the Indonesian student protests echoed among movements around the world – from Burma to Zimbabwe, Nigeria and elsewhere.

Much the same way, Chinese students seriously challenged the legitimacy of the ‘Heavenly Peace Mandate’ supposedly resting upon the government and parliament when they occupied Tienanmen, ‘The Great Square of Heavenly Peace’. No state government could tolerate such a pointed humiliation before the eyes of the world one minute longer than was needed. In Beijing, as in Jakarta, the government was desperate to act quickly to end the international embarrassment: five days in the case of Jakarta, a few months in Beijing.

In China, however, moral anger was not so specific and deep as to awaken popular and middle class movements, as happened in Manila and Jakarta. Certainly, the Chinese students and urban masses’ struggle for freedom was motivated by a general protest against a monopolistic communist regime. But Tienanmen lacked the great and specifically directed moral force manifested in the Philippines after the cold-blooded killing of the popular senator Benigno Aquino, and in Indonesia after the tragic death of students at Trisakti University in Jakarta.

Army

But if China’s model lacks certain crucial ingredients, the role its armed forces played could have happened in Indonesia too. Indonesian opposition leader Amien Rais claimed that the reason he called off a mass gathering at the National Monument on the early morning of May 20th was that one Indonesian general had seriously warned him: ‘We too can do a Tienanmen’. In the post-Suharto transition, uneasy and uncertain as it is, the ‘Chinese way’ remains a real threat.

Indonesia’s Armed Forces (Abri) played a decisive, yet very cautious role. Lt-Gen Syarwan Hamid, as vice chairman of parliament, gave permission to the students to stage a big protest at the Senayan complex. He would not have done this without consent from the top.

However, top level Abri leaders only moved reactively during the crucial weeks in mid-May. Abri commander General Wiranto seemed to play a waiting game. He agreed to ask President Suharto to step down only after the people’s protest had gathered momentum, and after some politicians – notably Coordinating Minister for Economy and Finance Ginanjar Kartasasmita, who had IMF leverage at his disposal – boycotted Suharto’s last attempt to save his regime by reshuffling the cabinet.

With Suharto gone, Abri got its first chance in years to act independently. But General Wiranto, once Suharto’s second longest serving aide, could only do so by trial and error. He did it with a lot of hesitation and, possibly, still under Suharto’s shadowy influence. A worsening economic crisis did not help Abri to act decisively.

Rivalry

As a big ally and key powerholder during the three decades of Suharto rule, it was only natural that Abri should face an internal crisis in step with the national leadership crisis. As in the Philippines, People Power in Jakarta tended to intensify already existing military rivalries.

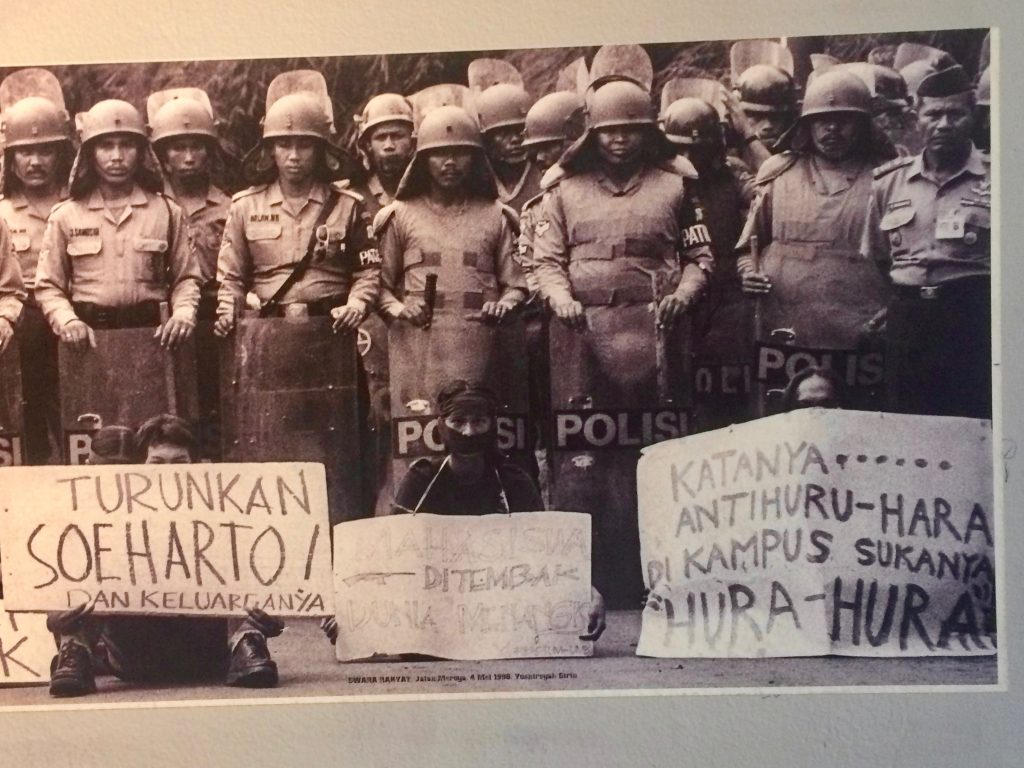

The racial riots and the burning of Jakarta on 13 and 14 May, following weeks of student protests, clearly suggested the intensity of those rivalries. Massive looting and burning left some 1200 dead. Hundreds of Indonesian-Chinese women were barbarically raped.

The tragedy was engineered, at least partly, by elements within the state, who hired hooligans known as preman from outside Jakarta. Some within the military elite clearly wanted to counter the reform movement by manipulating public frustration. They evidently hoped that, as in 1965 and early 1966, a strong man would arise out of the chaos to restore order, not necessarily to challenge the president immediately, but to open the way for a new leader with fresh legitimacy.

It became clear that Suharto’s son-in-law Lt-Gen Prabowo Subianto, commander of the Army Strategic Reserve (Kostrad), had tried to gain power only a day after Suharto resigned. He had civilian allies among Muslim radicals associated with the group Kisdi.

However, General Wiranto called his bluff by hastily moving him from his command post to the staff college. Following this sudden demotion, Prabowo tried that same evening to move ‘his’ Kostrad men to the palace, apparently to pressure President Habibie into taking sides against Wiranto. But this attempt too failed.

It has also been confirmed that elements of Kopassus, a special corps then led by the same Prabowo, was responsible for the kidnapping of activists in March. The purpose was to ensure that Suharto was reappointed as president. The state terror in May -the Trisakti killings and the racial riots – should perhaps be interpreted as acts of the same military faction and its civilian allies to defend Suharto, or at least to manipulate his succession for their own purpose. So Prabowo was Jakarta’s version of Gringo Honasan. Fortunately both failed. Although the Honasan-like game in Jakarta could not be played out openly, the essential ingredients, as in Manila, were there.

Both Honasan-like acts of state terrorism and the threat of massive Tienanmen-like reprisals will remain alive as long as the Habibie government or its successor fails to restore its domestic and international credibility and its ability to guarantee the people’s basic needs.

Moreover, as soon as Suharto resigned, Abri made it clear it wanted to avoid a power vacuum, and that it continued to claim a stake in the national leadership. ‘The most important prerequisite to reform is efficient and capable national leadership,’ said Abri chief of Socio-political Affairs Lt-Gen Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono recently. The message was delivered before a thousand top military officers only a week after Prabowo’s indisciplinary acts, the first such meeting since Wiranto took command.

More than anywhere else, pro-democratic civil society in Indonesia has to compete with the state apparatus to take the lead and decide on the agenda of reformasi.

East Germany

Lastly, Jakarta’s May Revolution exposed weaknesses within Indonesia’s own democratic movement. At the end of Annus Mirabilis, the European ‘Year of Miracles’ of 1989, a great number of students, joined by human rights- and church-affiliated organisations, marched in the East German cities of Leipzig and Dresden chanting Wir sind Das Volk (We Are The (sic!) People). This famous march led to the fall of Erich Honnecker’s communist regime in East Germany. The call effectively targeted a regime that had claimed to be the only true representative of the people.

The call for ‘Reformasi Total’ from Senayan against a regime which refused to do real reform, could have had deeper effects – not only the fall of Suharto, but also real action to fulfil the needs of the people and to start a democratisation process as in East Germany. If only Jakarta’s ‘May Revolution’ had not suffered so much from a Chinese-like imbalance between state and society, and from a Philippine Honasan-like internal military game.

Moreover as in Beijing, but unlike Manila and Leipzig, the pro-democracy movement in Jakarta lacked a solid political platform to lead the momentum of change. The student protest was too much insulated as ‘a moral force’. The politicians were too divided, the masses too little organised, and the state leadership crisis in May resolved too quickly to allow People Power to present an alternative force.

No single power was able to carry the new legitimacy from Senayan to its full consequences. Jakarta’s ‘May Revolution’ – including its weaknesses – was a direct consequence of Suharto’s three decades of repressive policies.

Aboeprijadi Santoso is an Indonesian journalist based in Amsterdam. He watched closely the recent events in Jakarta, in Manila in 1986-87 and in Eastern Europe in 1989-90.