He was a great scholar who mastered sixteen languages, learnt oriental cultures seriously and described them meticulously. But he was also a man of great adventure and ambition that made him part of the expansion of a colonial state to which he dedicated most of his works.

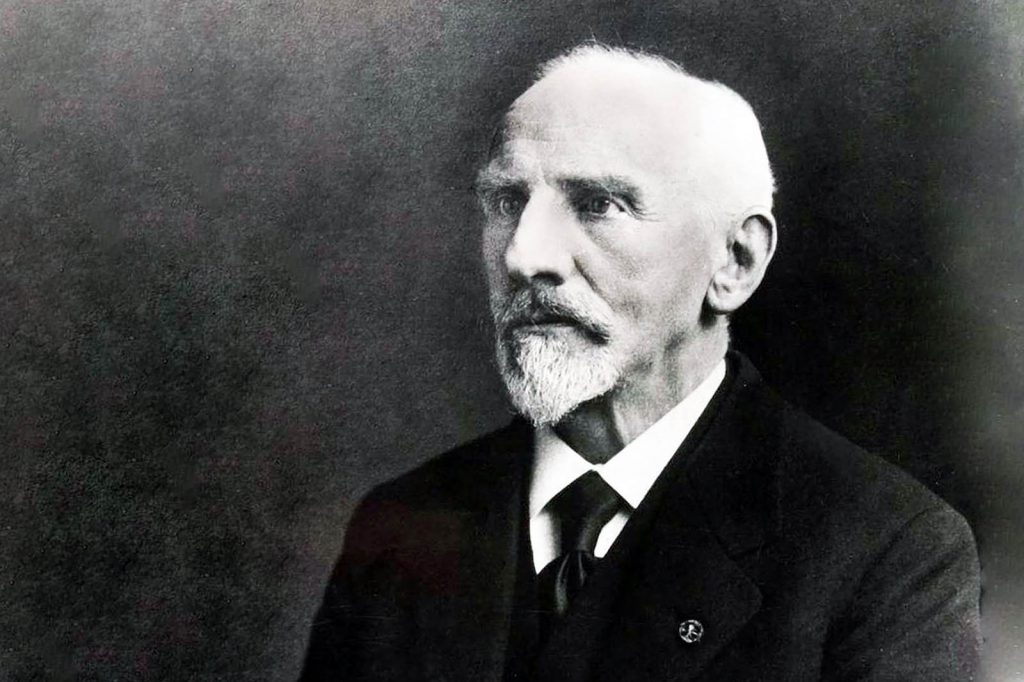

Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje (1857-1936) is Dutch most famous orientalist and expert on Islam of his time. His rich writings are preserved in Leiden and much has been written about him and his works.

Now a senior journalist has written a story of Snouck’s life and adventure in popular and attractive yet compelling way. Philip Dröge’s Pelgrim, Leven en reizen van Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje – Wetenschapper, spion, avonturier (Pilgrim, Life and voyage of Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje – Scholar, spy and adventurer), 355 pages, Spectrum 2017, is not intended as a full biography. He adds a list of numerous sources on which he bases his novel. Snouck’s complex life may defy an official biography, which indeed has not been written yet. *)

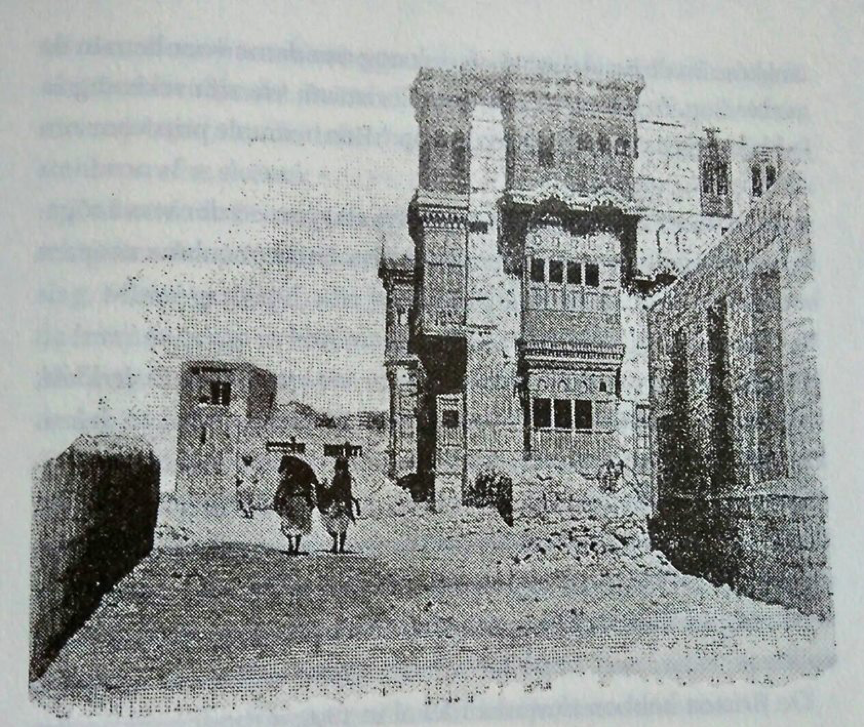

Instead Dröge offers a narrative of events describing, often in details, with verve and vividness, the dramatic encounters full of risk and danger as Snouck entered and lived in Mecca – the holy city, most exotic for Europeans, yet forbidden for non-Muslims.

Snouck knew only too well he had to go native, but, in the first place, had to get along safely with the Turks-Ottoman authorities who ruled the Arabian peninsula.

It was with such resolve that Snouck, as Dröge described it vividly, went through the circumcision only to find, with pain, his penis bleeding – creating mini islands of blood on the floor when the barber did his job.

And once he loudly read the prescribed verses of conversion before the Qadi (jurist), Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje “was no more”. (p.69) The young PhD from University of Leiden thus became Abd al-Ghaffar al-Laydini (The servant of The All-forgiving God from Leiden).

Snouck’s journey from Jeddah to Mecca, with a caravan of men and camels, his arrival in the holy city, and his life there, the problems he encountered and the drama’s he went through plus the dramatic personae he met with — all are told in a writing style that compels the readers to feel and ‘touch’ his adventure – like the story of his bleeding penis.

Going native for Snouck meant more than adaptation. He lived truly like the locals in terms of clothing, consumption and almost all aspects of daily life – including adopting an Ethiopean girl, whom he bought for 150 Austrian ringgit, as his home slave when slavery was actually outlawed in Europe.

In Mecca he studied under the guidance of prominent religious scholars like Sayeed (prophet descendant) Ahmad Dahlan – whose name was later adopted by the Indonesian Muslim who founded the Muhammadiyah. Snouck also became neighbor and good friend of Acehnese and Javanese communities who resided in Mecca. In fact he did espionage them. At the same time, from all of them, from his slave to the holy Sayeed, he gathered ethnographic details in his search to find what was then seen as “the secret of Islam”.

At a time of upheavals when rebel groups were involved in the name of Islam – also in Dutch East-India – Snouck’s work was of utmost importance. Indeed, his trip to Mecca was sponsored by the government in The Hague to acquire greater understanding of the Islamic world. His works on Mecca, written during a relatively short period of stay, made him famous among the world orientalists then.

Unfortunately, after a half year and because of some controversies around a pre-Islamic artifact found by a German geographer, in which Snouck was somehow involved, he had to leave Mecca for his own safety.

But it was the right time for The Hague to send Snouck to Aceh, that part of Dutch colony that produced most profitable black pepper now threatened by a Muslim rebellion led by Tgk. Chik di Tiro – whose relatives were well-known to Snouck from his time in Mecca.

By then he had definitely chosen to become part of the colonial state apparatus rejecting job offers from renown Oriental faculties in the UK and elsewhere – despite his fame in the academic world. Thus, on March 27, 1889 Snouck was ready for a journey to the northern tip of Sumatra with a secret plan only known to the Minister of Colonies in The Hague and the Governor General in Buitenzorg (Bogor).

The latter, however, decided to send Snouck to Banten where a number of Dutch and local officials were recently slaughtered by Muslim fanatics. It was in Banten and later in Aceh, it would seem, that Snouck was confronted with local dynamic of Islam and recognized natives who obeyed the authority and those who were rebellious.

Muslim natives were generally peaceful, but under certain circumstances they could mix social issues with Pan-Islamic imperatives apparently derived from utopian Caliphate ideas. Hence, not Islam, but political Islam, or certain forms of it, – Snouck was once quoted – is “verwerpelijk” (deplorable). A similar distinction Soeharto also applied in the earlier phase of the New Order.

But Snouck, being a key advisor, had by then been already deeply implicated in the actions of the colonial state.

When he started his mission in Aceh later, he proposed to stay away from the Sultan, his supporters and the Dutch community, and prepared a strategy to crush Tgk. Umar rebellion. He joined the Military Governor Jo van Heutsz in three-months long military expedition starting from Pidie in the east coast to Meulaboh in the west. They cut off the links between the rebels and the pepper fields so as to catch Umar and end his rebellion.

How proud Snouck was of his espionage, war adventure and achievement can be seen as he read the newspaper reports. While the Dutch media in the Indies celebrated van Heutsz as the war hero, Snouck “interprets the news differently. For him most important is that Umar was killed in the west coast, which meant that (Snouck’s) tactic worked. By closing in on Umar and other warlords, they no longer felt secure.” (p.258).

Yet Snouck concluded his sixteen years work in the colony disillusioned.The man who saw himself as “onaantastbaar” (powerful) now felt “gebruikt” (merely being used) in Aceh and Banten (p.296 & 301). Tired of collusion within the Dutch bureaucracy, he rejected the offer to become Governor of Aceh. In 1906 he returned to Leiden, back to the academic world.

When he became Rector Magnificus of the University of Leiden in 1921 he condemned in sharp criticism Dutch exploitation of the natives and called for an end to racial discrimination. His inaugural speech echos the famous cry Eduard Douwes Dekker aka Multatuli voiced in Max Havelaar (1859). He remained reluctant to talk about Islam and his career in the colonial bureaucracy.

The bitter truth is while he used the Dutch state to finance his ambition and adventure in Mecca, he consciously let himself being used as a prominent strategist for the sake of Dutch imperial ambition in Indonesia only to deeply regret it belatedly. He died in 1936 five days after he took exam on Acehnese language from his student.

Eighty years later everything Snouck had witnessed has definitely gone, Philip Dröge claims as he looks at modern Mecca and visits post-tsunami Aceh. Snouck’s former house in Mecca is now a big hotel garage and Aceh embraces Shariah more than ever.

The book is a fascinating reading even if sometimes dramatizing the portrait of a complex figure in different places. Snouck’s role in Aceh for example is beter narrated and explained than his story in Banten. The spelling of places is somewhat confusing or simply wrong – like denoting Garut as a city in Central Java.

One of the most intriguing questions, however, remain: was Snouck, son of Brabant (South Holland) Christian preacher, ever a faithful Muslim, spiritually loyal to his belief, or did he manipulate the religion or his faith for his own ambition?

He told his friend and admirer Cornelis van Vollenhoven that he now “klaar” (finished) with Christianity and described himself as being “anti-christen”, but he remained completely silent on “his” Islam (p.301). He was buried, facing the holy stone of Ka’bah, the same day he died – as Islam prescribed.

One scholar, Pieter Sjoerd van Koningsveld, however, believes Snouck’s conversion was unique because it was just temporary because he used Islam as a “convenient instrument”.**) From Dröge’s description, though, one might be impressed by the way Snouck enacted his ritual at the Ka’bah while seemingly suspicious of the holy zam-zam water at that, and sometimes consumed alcohol.

Perhaps, Snouck should be described as Dutch Muslim imperialist – although in terms of faith (aqidah), the truth – as they say – “only God knows”.

—————————

*) Cf. Christina Carvalho, Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje: biography and perception, MA thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2010.

**) Peter Sjoerd van Koningsveld, Conversion of European Intellectuals to Islam: The Case of Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje alias ʿAbdal-Ghaffār, Brill.(2016), URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1hd.8